Server with Login Exercise / Example

- Flask login docs: https://flask-login.readthedocs.io/en/latest/

- Using "Log in with social network": https://python-social-auth.readthedocs.io/en/latest/configuration/flask.html

- General Flask docs: https://flask.palletsprojects.com/en/2.2.x/quickstart/

TODO

- Get it to run. You need

pip install flask flask_wtf flask_login, andflask run. - All the relevant source code is in

app.py– it's the same as the SQL injection example, but with login and sessions added. - Connect to http://localhost:5000/ – it should redirect to a login page. Try logging in.

- Check the Flask login docs, and add a

logoutroute - Implement password checking. Now it uses plaintext passwords, stored as plaintext – find a secure way of storing passwords (i.e., with hashing and salt)

- Optional: The user database is just a

dict– you can change this to use the SQL database (just add a table and do database lookups instead of dict lookups) - Try restarting the server and reusing the login form in the browser. What happens? Why?

(was Tiny SQL Injectable Server Example)

This project contains a tiny webserver with a little database. It's supposed to be a (crude) group messaging app (e.g., like a Discord channel), but the web api is limited to just two operations: GET /search?q=<pattern> to search for messages, and POST /send with paramaters sender and message to send a message.

For example, with the server running, this link will list all messages: http://localhost:5000/search?q=* and this link will send a short message: http://localhost:5000/send?sender=Bob&message=Hi%2C%20Alice!

Fortunately, there's a very nice front-end included (at http://localhost:5000/) so you can hack the server without having to mess with sending HTTP requests yourself.

To use

You need to install these Python packages first – Flask, APSW, Pygments:

pip install flask

pip install apsw

pip install pygmentsStart the Web Server

Use the flask command to start the web server:

$ cd tiny-server

$ flask runIf the flask command doesn't exist, you can start use python -m flask run instead.

$ python -m flask run

* Debug mode: off

WARNING: This is a development server. Do not use it in a production deployment. Use a production WSGI server instead.

* Running on http://127.0.0.1:5000

Press CTRL+C to quitAssuming it works, you should find the web server in your browser at http://localhost:5000/

(For server apps that aren't called app.py, you can add the --app option: flask --app hello.py run)

WARNING: Don't expose this example server to the internet – it's horribly insecure!

Database

You don't have to set up a database server or anything – we're using SQLite, which is embedded in the program (it's bundled with the APSW library, so you don't have to install anything).

The database is stored in the file ./tiny.db – if you wish, you can install the SQLite command line tools and examine it. If you need a fresh start, you can just delete the file, it will be created automatically.

The Web Page

- The grey area at the top will show output from the server. The messaging app is in early stages of development, so the UI isn't entirely end-user friendly. The output from searching looks like this:

/search?q=* → 200 OK

Query: SELECT * FROM messages WHERE message GLOB '*'

Result:

[1, 'Bob', 'Hi, Alice!']-

At the bottom you'll find a simple form to interact with the server:

-

The Search field takes a search pattern to search for message contents – or do arbitrary database operations if you're an INF226 student

-

You can also add messages to the database with From/Message/Send.

-

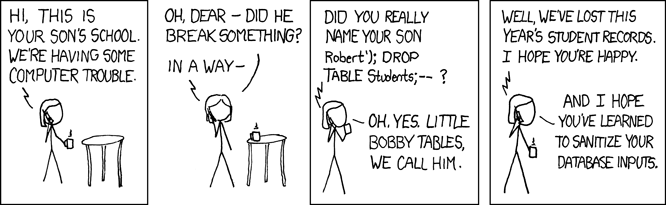

Inject SQL into the Search Query

- Use the Send button to see what a normal

INSERTstatement looks like, if you're unsure. - Try entering a search string that will add a new message. The server just inserts the search string between quotes

'…', so it's easy to trick it into running whatever you like. - You can also try the classic DROP TABLE trick. Just restart the server to reinitialize the tables (you can also delete the database file (

tiny.db) to start fresh).

For your convenience, the server will show you the actual SQL query it uses. This is not entirely unrealistic; you've probably seen (misconfigured) ASP.NET sites showing you a yellow error page with “Server Error in '/' Application” showing relevant bits of the source code / SQL query. That's a really bad idea, and could give an attack just the information needed to succeed with an injection attack. Never give any details in error messages from a network server!

Inject a new Annoucement

- The app also supports ‘announcements’ that will be shown on top of the screen. Can you figure out how to add an announcement without looking at the source code?

Close the Security Hole

SQLite and APSW (and practically any other SQL library) supports prepared statements:

cursor = conn.execute('SELECT * FROM people WHERE firstName = ?', (name,))

cursor = conn.execute('INSERT INTO people (firstname,lastname) VALUES (?,?)', (fname,lname))- Change

app.pyto use prepared statements, and check that the SQL injection attack no longer works.

Note: There are a number of other nasty security problems with code, so don't think it's safe just because we patched the SQL injection hole.

Hints & Tips

-

For successful SQL injection, you might need to make sure that the full query (with injections) has valid SQL syntax – i.e., you need something to ‘swallow’ the final

';from the original query. You can do this by ending your injected statement with--(which begins a comment) or a no-op command likeSELECT ' -

If you tried this with Python's builtin

sqlite3library (which is used in almost the same way asapsw), you'd find that the'; DROP TABLE…trick doesn't work – it simply won't accept multiple SQL statements in one query (so-called stacked queries). The same applies to many other SQL connection libraries, so the stacked query trick is unlikely to work on a modern system even if it's vulnerable to other SQL injection variants. -

You may sometimes need to know what tables are available in the database. There is no SQL standard way of doing this – there's typically a special command for this in the database shell, and often it's possible to access the schema (table declarations) from inside SQL. For example,

- In SQLite, use

SELECT * FROM sqlite_schema;(on the SQLite command line (sqlite), you can use.tables– but you can't run such commands through SQL injection) - In PostgreSQL, use

SELECT * FROM pg_catalog.pg_tables;(on the command line (psql), you can use\dtinstead) - For MariaDB / MySQL, theres a neat

SHOW TABLES;SQL command

- In SQLite, use

Automated Injection with sqlmap

sqlmap is “an open source penetration testing tool that automates the process of detecting and exploiting SQL injection flaws and taking over of database servers. It comes with a powerful detection engine, many niche features for the ultimate penetration tester, and a broad range of switches including database fingerprinting, over data fetching from the database, accessing the underlying file system, and executing commands on the operating system via out-of-band connections.”

It's written in Python and can be installed with pip:

pip install sqlmapWARNING: As with pwntools, never use sqlmap on a server without permission. It's illegal, unethical and may land you in a heap of trouble. Running it locally against this example server should be fine, however, and you can't ruin anything that you can't fix by deleting the database file and restarting the server.

To find injection exploits you must provide a URL with (at least) one parameter that might be suitable for injection. In our case, that might be /search?q=* (the parameter value should be valid and give a result, so sqlmap can tell the difference between a valid and invalid query). To try it, you can run something like:

python -m sqlmap.sqlmap --answers custom=N --technique=BEUS --tables -u http://localhost:5000/search?q=\* It will ask a few question (you can just accept the default answer), and it should then tell you it found a few exploits for the q parameter.

-

For more fun, try adding the

--sql-shellargument to the command line – that should give you access to the SQLite database. For other databases,sqlmapmay be able to read/write files or give you an OS shell on the server. -

For even more, see the

sqlmapmanual